The question of potential government involvement—and government conspiracy—in the bigfoot phenomenon is an ongoing one. While many researchers will acknowledge it, a handful will back away from it in the same manner Krantz (1999) acknowledged the “lunatic fringe” as an adjunct of the bigfoot phenomenon but dissociated himself from it at every turn. The problem with conspiracy theories and conspiracy theorists is the fringe or extremist elements associated with them. Personally, I have always viewed the question of government involvement as a dead end. If only for the sake of argument answers might be out there, I see little to no chance that they will ever be revealed despite avenues such as the freedom of information act.

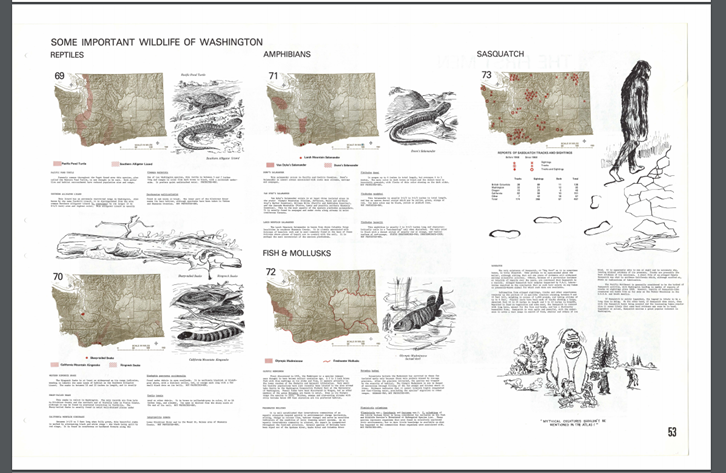

Laying aside conspiracy theories, raising the question of government interest is not an altogether unproductive one since at least one government agency was collecting—or at least collating—sasquatch data in the 1970s—the United States Army Corp of Engineers. Many bigfoot enthusiasts will already be familiar with the publication of the 1975 Washington Environmental Atlas by the Corp of Engineers due to the entry on page fifty-eight devoted to the sasquatch. The entry is written in such a way that the existence of the sasquatch is left open-ended, which is remarkable since mainstream scientists of the day were already dismissing any such possibility. What is intriguing about the entry is it indicates a potential early split in the attitude of at least one government agency—plausibility—versus the dismissive attitude of science.

Some critics have scoffed that the entry has any significance beyond being a one-off event, a publishing quirk if you will by a handful of insular Corp employees under the direction of Dr. Steve Dice, editor of the atlas, no more representative of—or connected to—the government than any outside contractor. While that possibility should be weighed, the extensive academic review process, endorsements by the governor of Washington of that time, Daniel Evans, as well as Colonel/district Corp engineer, Raymond Eineigl, among others, and the editor’s note in the atlas argues against it:

The [habitat] ranges and [animal] texts are based upon the current knowledge of many contributors and of reviewers contacted in Federal and State resource agencies and in local colleges and universities, and by contact with private individuals who have expert knowledge of these species. (United States Army Corp of Engineers, 1975)

It is equally plausible that any further research was secreted from that point forward, whether in the Army Corp of Engineers or another agency, due to the public response the atlas unwittingly provoked, the Associated Press picking up the story, which was reprinted in newspapers like the Washington Star-News. The atlas was, after all, published as “part of a national pilot test effort being conducted to explore the environmental information needs of planners” (United States Army Corp of Engineers, 1975). If the latter is the case and secrecy pursued, the question almost impossible to answer is what has become of government interest in the phenomenon since the mid-1970s?

The 1975 atlas was a comprehensive scientific tome and endeavor. Not much more than the $200,000 cost at the time (Engineers Corps book recognizes ‘Big Foot’, 1975) is needed to demonstrate that it was a serious undertaking. Years in compilation and review, the Army Corp viewed the second edition of the atlas as a thorough and accurate reference source, whose main objective was to collect environmental data of state or national importance. It was not viewed as a static project, but one that was forward-looking, subject to modification as data continued to accrue and data collection methods improved. Early identification of environmental resources was its stated goal to enable appropriate environmental assessment, management, and planning (United States Army Corp of Engineers, 1975). In this regard, the sasquatch entry coincides with the objectives of early identification, continued data collection, and the forward-looking nature of the atlas. It seems less an outlier and more logical fit when viewed in this context. While it may have been a public risk to include the entry in an inventory of consequential or endangered fauna, overlooking it may have been the greater scientific and environmental mistake from the standpoint of an editor like Dr. Steve Dice.

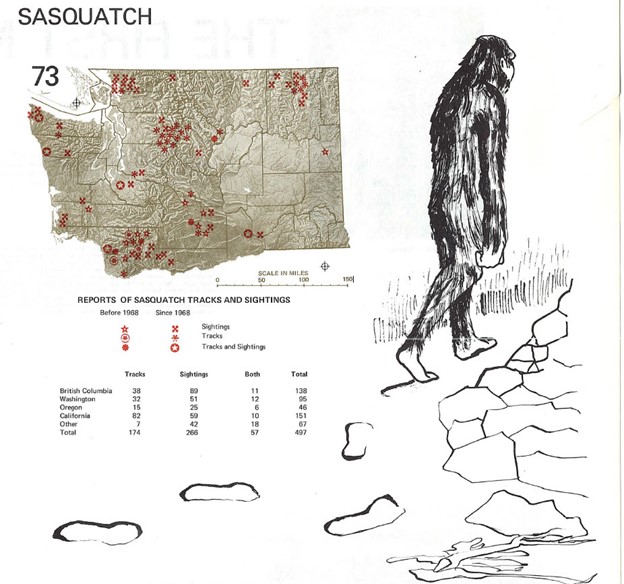

The sasquatch entry indicates that footprint data was the most convincing, citing measurements from casts ranging from 14 to 24 inches in length and 5 to 10 inches in width. The footprint data is charted along with sightings data in the states of Washington, Oregon, and California, the Canadian province of British Columbia, along with a column for Other for an aggregate total of 497 track/sightings. The data exactly corresponds to a chart from page fifty-eight of John Green’s Year of the Sasquatch published in 1970. This suggests that whatever data collection the government was conducting in this era, it was heavily reliant on the data of an outside researcher, namely John Green, and it was taking such research efforts seriously. Sightings data also indicated that the sasquatch was endemic to S. America, as well as Asia, the atlas specifically noting sightings in the Pamir Mountains of the USSR; the latter is not an insignificant detail in the context of the Cold War.

The atlas’ treatment of the Patterson-Gimlin film also breaks with scientific attitudes, concluding it “shows no evidence of fabrication.” Why it deviates from consensus scientific views at the time that the film was hoaxed is a mystery. Was the editor of the Atlas, Dr. Steve Dice, an unusually open-minded man of science or did he have other information available to him? Was Dr. John Napier’s (1973) conclusion that there was “nothing in the film to prove conclusively it was a hoax” simply repeated here, when, at best, Napier’s views of the film were full of contradictions that argued as much for hoaxing as against it? Or did someone or some persons within either the Army Corp of Engineers or another agency view the film and offer such conclusions? There seems no reason to deviate from scientific consensus at the time that the film was hoaxed yet this simple reference to the Patterson-Gimlin film does just that.

The statement in the Atlas that FBI laboratories had examined potential sasquatch hair that did not match any known animal was the most controversial. It prompted bigfoot researcher Peter Byrne to write a letter to the FBI asking for clarification on the matter, “to set the record straight, once and for all…”(Bigfoot part 01 of 01). In what some might interpret as a bit of obfuscation, the FBI’s follow-up letter to Byrne stated that the agency was “unable to locate any references to such examinations in our files”; Internal FBI memos also indicate Dr. Steve Dice “was unable to locate his source for the reported FBI hair examination” (Bigfoot part 01 of 01). The FBI did, however, agree to Byrne’s subsequent request to examine potential sasquatch hairs he had obtained; Byrne’s request was granted “in the interest of research and (legitimate) scientific study” (Bigfoot part 01 of 01). The FBI ultimately determined the hairs originated from the deer family (Bigfoot part 01 of 01). Whatever one makes of the FBI’s response to Byrne’s request “to set the record straight” (Bigfoot part 01 of 01), accepting Byrne’s hair sample for examination is another indication differences existed in government and scientific attitudes toward the sasquatch in the 1970s.

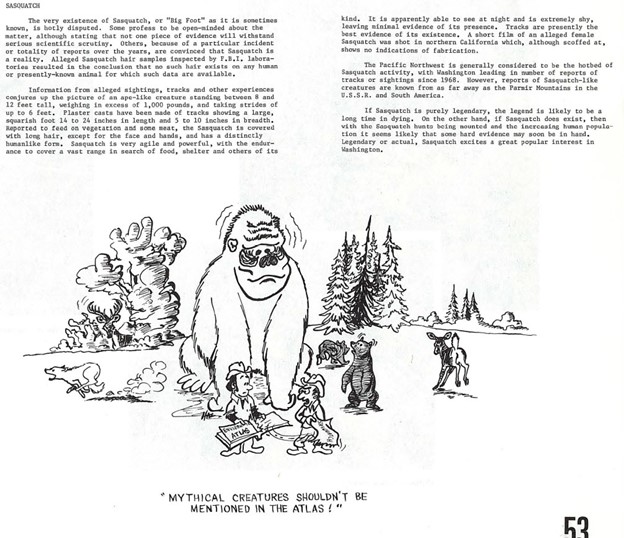

The public face of government attitudes toward the sasquatch begins and ends with the publication of the atlas, incredible in itself, considering it is just one small entry of some 350 words, a map of the state of Washington overlaid with sightings and footprint data, one chart, and a sasquatch sketch that accurately captures such details as the hirsute form, long arms, brow ridge, and receding forehead described by eyewitnesses. Of course, there is the inclusion of the cartoon as well, one that, on superficial reading, has given academics reason enough to dismiss the effort as lacking in any real substance. But all the cartoon does is anticipate controversy and the open-endedness of the sasquatch question. Humor is both an easy way to reach an audience and put it at ease. It does not contradict sasquatch plausibility or the known data from the period. If one was so inclined to analyze the cartoon, an ironic interpretation—something no doubt lost upon most academics—could very well be that the sasquatch would not be included in the atlas if it was merely a mythic animal, or at least an animal for which there wasn’t sound evidence to support its existence.

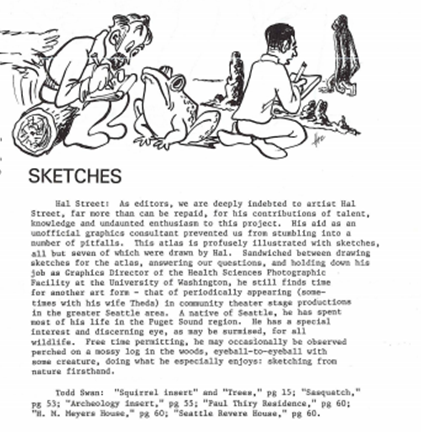

It should also be noted that the sasquatch is also mentioned on page 101 of the atlas, under the Skamania County heading, the location of Ape Canyon, notorious for reportedly being “one of the first places where white men sighted a ‘Big Foot’” (United States Army Corp of Engineers, 1975). On page 114, there is an additional illustration of an artist, pen and paper in hand, observing a bigfoot walk past to demonstrate Hal Street’s penchant for “sketching nature firsthand” (United States Army Corp of Engineers, 1975), comical no doubt but the point being that the main sasquatch entry was not just a one-off event. The other sasquatch references point to weighted decision-making and against rogue publication. Hal Street was the atlas’ primary illustrator.

After this lone entry in the Washington Environmental Atlas, other than an Air Force survival training map that I have so far been unable to authenticate that features sasquatch among the local fauna, potential evidence of government interest almost entirely dissipates. The most logical means of obtaining information from various government agencies is by filing a request through the Freedom of Information Act. Yet it has proven to be largely unproductive. Bigfoot researcher David Paulides has either filed requests or directly contacted agencies such as the USFS, Department of Interior, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, National Park Service, and the California Department of Fish and Game. The California Department of Fish and Game, for example, provided a hodge-podge of items in response, among them 22 clipped newspaper articles about bigfoot, many dating from the 1970s, 23 letters written to the DFG, largely from the public, concerning bigfoot matters or sent in reply by the DFG to inquiries about bigfoot, and four copies of the Bigfoot News from the 1970s; there are eight bigfoot sightings events in this documentation, some sent in by eyewitnesses, including a letter from one individual describing multiple bigfoot encounters (Paulides, 2008). The few items in the DFG collection that might be of greater value are either missing context, pages, or related information.

In a follow-up interview by Paulides, Eric Loft, Chief of the Wildlife Branch, California Department of Fish and Game, states this is the only “bigfoot file” and information he is aware of (Paulides, 2008). Loft is not aware of the department having any bigfoot pictures, hair, tissue, or a body, but adds “on each of these issues I’m not positive that we don’t.” (Paulides, 2008). Chief Loft further states, “If it isn’t an animal described in the Fish and Game Code or in regulations set by the Fish and Game Commission, then we likely have little jurisdiction” (Paulides, 2008).

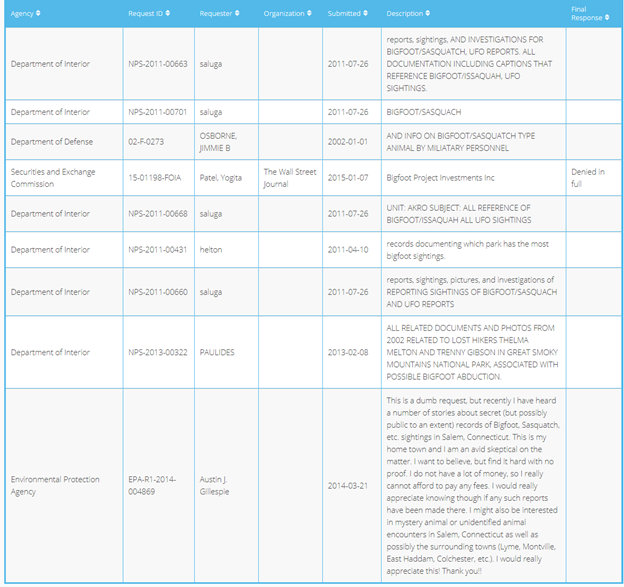

Other researchers or individuals have filed FOIA requests with agencies such as the FBI and CIA, the previously documented Peter Byrne/hair analysis requests being the only substantive documents released by the FBI. Government agencies will log such requests and in some cases the log requests are public, as in these FOIA requests pertaining to bigfoot made to the Department of the Interior, Department of Defense, and the Environmental Protection Agency:

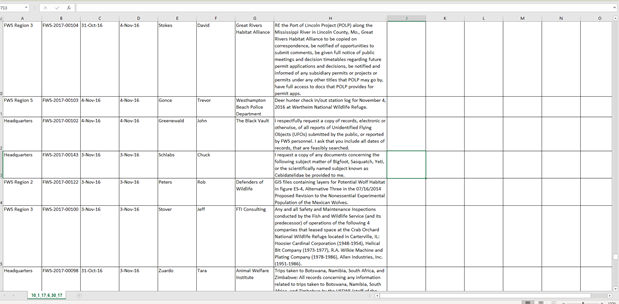

Log files from the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service are often made public as well, as in this file with the middle row showing a request for bigfoot documents:

Often multiple requests have been made to these government agencies over the years by different individuals or organizations, so if anything meaningful was released, it would have certainly made it into the public eye by now.

As with so much of bigfoot research, that leaves eyewitness testimony of government involvement in bigfoot sightings as the main avenue of productivity, which raises the same questions of reliability, especially to skeptics only superficially familiar with the eyewitness psychological literature. Ultimately, a new or classified or newly unclassified document—should one even exist—that proves government involvement is as likely to come into the public domain as raking the soil in some random spot and unearthing a bigfoot tooth or jaw bone fragment. Hypothetically, if intel was classified in the first place, it will remain that way for a reason.

None of this is to suggest that I believe such documentation exists, because, to my mind, if the government, with all its resources, doesn’t have better data than what has been published by accomplished authors like John Green, then the government is largely incompetent, and who can rightly argue against this last point? I’ve always leaned strongly in this direction—toward the government lacking anything in the way of answers surrounding the bigfoot phenomenon occurring in its own backyard. However, one potential flaw in this way of thinking is that it puts far too much emphasis on elected office—and the general incompetence and malaise the public often associates with elected officials—and not enough emphasis on the Dr. Steve Dice types in government employ, men and women of science, credentialed, data and analysis driven, individuals who escape the public eye, who are equally hardworking and dedicated and, once in a while, even brilliant, whose work behind the scenes we know little to nothing. Keeping these types in mind, some of whom are even in possession of security clearances of varying degree, recounting three of the most intriguing incidents of eyewitness testimony involving bigfoot, the government, and often government security measures becomes at least expedient despite the overtones of falling into the rabbit hole that each conjures.

Thom Powell’s documentation of an incident involving wildland firefighters finding a severely burned bigfoot that occurred August 7, 1999 at Battle Mountain, Nevada is the most comprehensive. The bigfoot suffered burns over large parts of its body, enough that it “had given up” (Powell, 2003). The anonymous eyewitness, a federal employee with EMT knowledge, known only by the pseudonym of “Marty,” was on the scene along with some twenty other federal employees; a medical team worked on the bigfoot (i.e. “patient’) administering Demerol, morphine, plus essential fluids (Powell, 2003).

During the treatment of his wounds and the efforts at life support, the patient communicated with moans, groans, and grumbling. Bowel sounds were heard by Marty, who was as close as three feet from the patient. No language-like vocalizations were heard. The patient responded to touch; specifically, patting and stroking to calm him. (“You’re not going to find an ape or monkey responding the same way” [Marty direct quote]). Two or three times Marty mentioned that the patient was especially responsive to a young Native American woman who started ministering to him right from the very beginning. The patient was removed from the scene in the back of a utility truck, not an ambulance. Marty said an ambulance would have alerted townsfolk and possibly news reporters, thinking that a firefighter had been injured (Powell, 2003).

The main traits Marty ascribed to the bigfoot was that it was seven feet tall, covered in short hair, head large and “heavy boned,” with large lips, and ears with attached earlobe; the hands were huge, five fingers with an opposed thumb (Powell, 2003). “The sexual features are those of an uncircumscribed male, matching the human anatomy…He [Marty] felt he was in the presence of a very human type creature” (Powell, 2003).

Marty concluded his interaction with a BFRO curator by stating, “Word is there is still life” (Powell, 2003).

Marty, in a follow-up email initiated by Powell several years later, stated that classification was assigned to the incident and he signed an affidavit under the Department of Interior and U.S Forest Service:

- Confidential under felony arrest and jail time.

- Immediate loss of Government service rank, loss of retirement, and benefits. (Powell, 2003)

If indeed such an incident occurred, with classification, any supporting documentation will not be released under FOIA. Documents that fall under the domain/purview of national security, foreign policy, agency procedure and practices, personal privacy, and law enforcement are FOIA exempt, and one or some combination thereof may be applicable here and can be more broadly applicable than a cursory knowledge might suggest. It is an open question whether a lower-level government employee fulfilling a FOIA request would even have access to such a document, and, to my mind, an unlikely one. Hence, the commonly worded refrain in any FOIA response that a search for documents was conducted in all reasonably known locations they might exist, etc.

The Battle Mountain incident was ultimately rejected as a hoax by the BFRO curator who handled it because Marty reported that the area was bulldozed afterwards; apparently the curator felt this was too convenient a cover story since the location could not be correlated with any potential evidence (Powell, 2003). Powell (2003) objected to the hoax conclusion due to the myriad details the witness provided, his demeanor, and EMT knowledge among others; Powell also found it logical for a government agency to bulldoze the area to conceal evidence if that was the objective.

This is only my suspicion, but I don’t think the Battle Mountain incident was rejected as a hoax based on the bulldozed site alone. The eyewitness’ description of the bigfoot is too humanlike for prevailing researcher attitudes in 1999, attitudes still strongly endemic today with bigfoot viewed as a very apelike descendant of Gigantopithecus. The anatomical description of the bigfoot, hand with opposed thumb, genitalia, and its responses to touch failed to meet expectations and was further reason to reject the testimony. Although I say this with a great deal of reserve, owing to the circumstances of the testimony, involving clear government intervention and secrecy, the distinctly hominin traits described by the eyewitness and potential classification in the Homo genus gives it greater credibility in my analysis—not less—at least in this one aspect.

Another incident, in a similar vein of government conspiracy and strong-arm tactics was reported by Fred Bradshaw. According to Bradshaw, his father witnessed several bigfoot carcasses being flown out of the Mt. St. Helens region by helicopter after the eruption of May, 1980 (Crowe, as cited in Coil Suchy, 2009). Most problematical about this report, which has taken on near mythic overtones, is it is second-hand, never desirable as facts can be distorted or lost in the retelling, and the initial eyewitness is not there to answer logical follow-up questions or to be “cross-examined” if inconsistencies in the story develop. For these same reasons, second-hand reports can also be more susceptible to hoaxing. The conveyer of the report could be either hoaxer or hoaxed himself. In examining this report closely, the inconsistencies mount rapidly.

The main narrative given by Bradshaw is that his father, a [security] supervisor[1] in private employ with Weyerhaeuser, was instructed to drive north toward the company’s Green Mountain [lumber] facility after nearby Mt. St. Helens violently erupted; his father was in a meeting twenty-three miles south in Kelso, Washington at the time (Crowe, as cited in Coil Suchy, 2009). The Green Mountain Weyerhaeuser facility, located in Toutle, Washington, is approximately 35 miles northwest of the Mt. St. Helens area via route 504. Unsurprisingly, “like most, he wasn’t allowed to go very far because of the mudslide coming down the river” (Crowe, as cited by Coil Suchy, 2009), though inexplicably Bradshaw makes it to Toutle eventually.

In what seems to me a very implausible chain of events for private security personnel amidst what can only be a government and emergency response operation, Bradshaw is instructed to initially “watch mud flow” while also helping with evacuations. “Then he was sent to the area of Spirit Lake to keep people out” (Crowe, as cited by Coil Suchy, 2009). Aside from questions of who ordered Bradshaw there, what qualifications he possesses, and the logistics of how he got there, especially with mud flow pushing the Toutle River twenty-one feet above normal at one point, Spirit Lake was less than 5 miles from the epicenter of the Mt. St. Helen’s blast and in its direct path. The lake and its shores were apocalyptic in all aspects, with many trees and animals incinerated. Pyroclastic flowed into its south shore and toxic volcanic ash—the same ash responsible for asphyxiating the majority of the 57 people who died in the blast—rained down over an area well beyond its shores. Tragically, volcanologist and USGS employee David Johnston, who had been monitoring the early signs of volcanic activity from a ridge six miles away, died near instantly from the unexpected side blast, which was triggered by a 5.1 magnitude earthquake (Bagley, 2018). Certainly, no one was going to Spirit Lake, likely impossible anyway, and there was no need for Bradshaw to be there to prevent others from doing so. His presence there could only amount to reckless endangerment to his own life. When a second blast occurs, Bradshaw reports in and is “told to get out of there” (Crowe, as cited by Coil Suchy, 2009).

The absurdity of Bradshaw surviving a second blast in such close proximity to the mountain and another round of toxic ash aside—or at least the reckless endangerment for his own safety this would have posed—he is then placed in charge of a helicopter landing zone until “all the people and bodies were taken out” and “the National Guard was brought in to clean up,” whereupon the Guardsmen placed dead animals they hauled out in piles (Crowe, as cited by Coil Suchy, 2009). At this juncture, Bradshaw is reassigned (once again) to take “charge of one pile of dead animals in particular” that is already being guarded by “armed U.S. National Guard personnel” (Crowe, as cited by Coil Suchy, 2009). I fail to see what Mr. Bradshaw, a private security officer, offers in the way of authority or further security presence during this government operation as described. He can only be a liability and a security risk. The narrative concludes with the following:

When the tarps were removed [from the pile of dead animals], he was amazed to see that the bodies were those of sasquatch. Some badly burned and some not. They were placed into a large net and placed in back of a truck, which was then tarped over. His father asked a guardsman what would happen to the bodies, and the guardsman replied, “They’ll study them or whatever. I don’t want to know. It’s like other stuff, you don’t ask.” Later that day, his father and the rest were debriefed, told not to talk about what they had witnessed there that day, and sent home. (Crowe, as cited by Coil Suchy, 2009)

The events as described are simply impossible. I don’t know what the timeline is here—it reads as if it all happened over an extremely busy week—when it is equally illogical if it took place over a month or two from the initial blast. However, the second, smaller Mt. St. Helens’ blast occurred on May 25, pointing to a timeline of a week. Inconsistencies, which give rise to absurdities, abound in the narrative, especially when the force of the initial eruption is taken into account: blast zone 230 square miles, debris and rock thrown like projectiles, trees leveled, toxic ash spewed for miles, pyroclastic flow, mud flows, rising rivers, roads/highways shut down for varying amounts of time, flights cancelled due to visibility, 7,000 estimated animals killed. The commingling of a private security employee with government emergency response units, agencies, and the National Guard that he is neither authorized, trained, qualified, or paid by for that matter is equally damning to the narrative. Emergency response teams and the National Guard would have had far bigger issues than cleaning up deer and elk carcasses from the surrounding forest that first week, not to mention the absurd amount of time, logistics, and finances required for such an implausible mission. In fact, the skeletons of deer and elk were found months later at various locales within the zone of destruction, often precisely where the herds had succumbed to the effects of the blast, with academic research and field studies of the remains conducted when it was safe to do so, the scientific objectives varying, as evidenced by Lyman’s Taphonomy of cervids killed by the May 18, 1980 volcanic eruption Mt. St. Helens, Washington, U.S.A., for example.

Fred Bradshaw was a retired deputy sheriff and, on first impression, an ideal witness, who was regularly active within the bigfoot research community in the 1990s. Researcher Bobby Short described him as “colorful” and professed great faith in him; other researchers, it seems, were more dubious (Short, 2010). A closer examination reveals he claimed at least seven bigfoot encounters, only two of which were documented by John Green in his database. Bobby Short documented most of the others. Short also mentioned Bradshaw could find bigfoot tracks practically at will. Anyone familiar with my research will know I am highly skeptical of someone who claims a multitude of bigfoot encounters—not that it is impossible—but the odds quickly amass against it. Add to this someone who can find bigfoot tracks at will (see my Tracking Bigfoot essay this website) and my skepticism increases tenfold. Suddenly, this is a combination only a few men have claimed, and, of those, the evidence points to hoaxing as the explanation, not any special aptitude or talent.

The two encounters documented by John Green include a bigfoot that tossed a large branch into Bradshaw’s camp,[2] and a road encounter that required Bradshaw to throw his jeep into reverse to escape a female bigfoot that stepped toward the vehicle. One of the many bigfoot encounters that Bobby Short attributed to Bradshaw had him pointing out an “unbelievably white” bigfoot to a group of bigfoot enthusiasts; the bigfoot hid the moment he did so (Short, 2012). The bigfoot was “like a lighthouse this animal was so white it didn’t look real” (Short, 2012). Short (2012) also mentioned Bradshaw encountering a brown bigfoot that smiled as it looked into the front window of his vehicle as it walked past. This behavior was repeated during another encounter when a dark bigfoot—“so dark that the only details visible happened to be the whites of its teeth”—smiled at him near a local army base (Short, 2012). What Bradshaw did in response is not mentioned. During another incident, when a bigfoot shook his camper while he was inside, Bradshaw summed up the situation with “…it wasn’t funny” (Short, 2012). A journalist from the Daily Herald also reported that Bradshaw had a bigfoot encounter in the 1950s, while just a child camping with his family near Mt. St. Helens (Moriarity, 2000).

With the encounters Bobby Short details, there is an odd pattern of bigfoot so extreme in color that other details are impossible to discern, as well as the odd smiling behavior. Often there is an unconscious self-confession in the narratives of hoaxers, as in the “lighthouse” bigfoot “so white it didn’t look real” (Short, 2012), since likely it was not real, a fabrication. Bobby Short (2012) attributes the smiling behavior to a kind of aggression, but I think the more likely scenario is it did not happen, just as the encounters did not likely happen, Bradshaw being “colorful” but at the same time self-important. Bradshaw also made claims about bigfoot that are not only unsubstantiated, but reckless, stating “they have been known to roll in the blood of the animals they kill and to spread their own feces on themselves to keep the unknown away” (Moriarity, 2000).

The ultimate truth about Bradshaw in my analysis is that he was a researcher in name only, given to wild conjecture, tall tales, and there can be no mincing it—hoaxing, despite his background in law enforcement. Sometimes, there is that rare exception, someone on the wrong side of the law so to speak, as in the case of Fred Bradshaw. He follows the typical hoaxer’s pattern of repeat encounters or repeatedly turning up evidence far out of proportion to others. While his claim of the government concealing bigfoot corpses after the Mt. St. Helens’ eruption has endured, it should not have. While it is possible some bigfoot were killed in the blast, his narrative about his father witnessing bigfoot corpses doesn’t get us any closer to the truth, and certainly not the truth if the government could at all be involved.

Inspired by Bradshaw’s tale of a government conspiracy, Douglas Kenck-Crispin (2016) sent a freedom of information request to the United States Department of Agriculture/Forest Service to determine if bigfoot bodies were recovered after the Mt. St. Helens’ eruption. The Forest Service’s reply was as follows:

The Wildlife Biologist for the Gifford Pinchot National Forest conducted the search for responsive records in all locations a reasonably knowledgeable professional would believe the records would be located. No responsive records were located for Items 1 or 2 of you[r] request as there were no documented reports of big foot or sasquatch carcasses and there were no projects to attempt to locate and/or recover any bodies.

Regardless of whether one is inclined to believe Bradshaw’s account, the Forest Service’s reply is not all that surprising. If the incident did not happen then no records exist to retrieve. If there is any truth to other rumors—Coil Suchy (2009) details another account of a crane dredging up two bigfoot corpses after the blast for example—then the wildlife biologist who undertook the record search would likely not have access to any such documentation in the event of classification.

Of no dispute is that neither the Battle Mountain account of the severely burned bigfoot or Bradshaw’s narrative of his father being an eyewitness to bigfoot corpses can be cases of eyewitness error. The Battle Mountain emergency response scene lasted three hours (Powell, 2003). The eyewitness, “Marty,” had an intimate prolonged view. Bradshaw’s narrative unfolds over the course of a week. These accounts are either factual or fabrications, which at least eliminates any argument that the eyewitness made a visual error. While I think the Bradshaw account is clearly a hoax, the Battle Mountain account—if indeed it is a hoax—is more nuanced and intricate. It requires somebody who was likely at the scene of the fire (or is well acquainted with wildfire emergency response) to inject a prolonged testimony of a bigfoot administered medical treatment, while knowing enough of bigfoot anatomy from the literature to be convincing, while also being able to project convincing bigfoot behavioral responses—the last being the most difficult to do. I am incapable of judging the medical procedure testimony for potential errors, though Powell (2003) received feedback from an EMT that this was valid. If the Battle Mountain incident is a hoax as the BFRO concluded, it is a solidly constructed one. With all the hoaxers that I have deconstructed, there is a “body of work,” i.e. a number of sighting events/plaster casts that can be held up to overall scrutiny with far greater chance of inconsistencies being exposed, as in the case of Fred Bradshaw, Glen Thomas, or Paul Freeman. As I have stated before, hoaxers hoax or fabricate repeatedly. They keep going back to the well. There is no body of work here, or other reported incidents that can be knowingly attributed to “Marty,” unusual because hoaxers have a psychological need to take credit for their work and the false accolades that come with it. It is the very reason they are in the game. Regardless of whether the site was bulldozed, it was unfortunate it was not investigated. In the very least it could have been determined if twenty emergency response firefighters and personnel, associated medical equipment, and vehicles could have been on this site at the same time, where this site was in relation to surrounding fires, the practicality thereof, and the practicality of the terrain. Steep mountainous terrain may have been enough to discount the entire testimony. A bulldozed site could also be verified, and whether it was done in some practical response to the fire, such as to “cut a line” to quote the lingo given to me by a wildland firefighter and create a fire break, or appeared to have been done for some other reason.

Another incident that falls under the potential realm of government interest in the sasquatch—actually, if the eyewitnesses are correct it goes beyond interest and falls under the category of advanced study—comes from a report sent into Steve Isdahl (2020) and published in his recent book. Isdahl’s stake in YouTube celebrity where he reads emails sent to him by those claiming a bigfoot encounter may lead to skepticism of the book, however. I’ll admit to having my own reservations initially, which even among self-published bigfoot books seems hastily put together, lacking much semblance of being proofread, edited, or, for that matter, “value added,” i.e. containing anything of substance or insight by the author. That being said, after my initial skepticism, there was a clear pattern to the reports in the book. They were almost exclusively sent in by avid outdoorsmen, hunters, even hunting guides like Isdahl himself, many ex-military and several others in law enforcement or former law enforcement officers. Evident when reading these emails was that these individuals felt a bond with Isdahl due to his wilderness, hunting, and guide experience, and were opening up and conveying their testimony in a way that was uncommon among a more tight-lipped stoic breed of men. Several related that when they attempted to share their experiences with a relative or friend, their accounts were dismissed outright or, worse, ridiculed, and they never spoke of it again. For these reasons, it is an especially important group to have added testimony from because it is a cohort likely proportionally underrepresented in the eyewitness literature versus cumulative outdoor experience. For the most part, the reports were consistent in describing bigfoot anatomy and behavior, sync well with the known literature, and even expand upon and/or reinforce bigfoot behavior to an extent.

The report of note in Isdahl’s book was submitted by an outdoorsman and fisherman who made annual excursions into the Florida Everglades, along points of the Miccosukee River and associated canals, by dragging his boat through weirs too shallow to motor through (Isdahl, 2020):

I was pulling my boat, 16’ Jon boat, and my buddy Joe was standing up in the boat on gator watch. With that said, if Joe made any kind of sound, motion or gesture, I would be in the boat in less than a second. That’s what happened, Joe was trying to get a word out but couldn’t make his mouth, vocal cord or something work. Now I’m in the boat, and Joe points to the bank where an animal or creature stands with a small alligator in its right hand, maybe 40 yards away. In 2 steps, it was out of sight in the thick low brush. This wasn’t a seven or eight-foot-tall thing, more like less than 6 [feet], muscular with balls of reddish hair hanging on it as if there had already been more that had fallen off, maybe shedding. Joe told me when he first spotted it, it had an alligator leg in its left hand and was eating it.

Now for the part that keeps us from telling others about that day that changed both our lives. We both could see a thick collar of some kind around its neck. It looked to be metal with leather, not 100% sure what it was made of as some of it was covered in neck hair. We both believe it was a tracking collar. I have searched the internet for years now and have never come across an encounter like ours, have you?

My hope is that if you share this, others may come forward that have seen the same thing. If there was a prayer of the animal being a bear or an escaped monkey, whatever, I wouldn’t be wasting your time. This was definitely the same animal others have spotted in south Florida that they call swamp ape. (Isdahl, 2020)

The eyewitness in this report seems to be genuinely struggling to put his sighting in context. This might be the only report I’ve read where the eyewitness is struggling less with the sighting of the “swamp ape,” and more with the ramifications that the collar around its neck suggest, inferred to be a tracking collar. The high strangeness of the sighting the eyewitness no doubt experienced is made exponentially stranger still by observing a “tracking collar.” If the eyewitness is correct in this observation of the collar, which is corroborated by his friend, reducing the likelihood of error, it must mean that other individuals have been in close contact with the sasquatch to place it there, which can only mean the hominin was subdued and restrained in some way and for some time. If so, other implications compound rather dramatically. It can only be an effort that requires time, planning, organization, financial commitment, and, most importantly, a prior knowledge of these hominins—in short, the earmarks of an organization operating under extreme secrecy. It seems highly unlikely to be a private undertaking, which only leaves a government funded effort of some sort.

In truth, I find myself walking back from any such conclusions. Certainly, an observational error on behalf of the two eyewitnesses where they mistakenly saw a collar that wasn’t there—maybe some unusual configuration of neck hair or shadow instead—and the whole issue dries up. The description of the collar being thick, made of leather and, especially, metal seems to belie such a conclusion. Metal alone is a stark contrast to hair, flesh, and skin. It seems a difficult mistake for two men to make in unison.

That doesn’t seem to leave much else other than a hoax they both agreed upon. Scrutinizing the testimony more closely, I can’t find any references to the Miccosukee River or place it on a map of Florida, though a portion of the Miccosukee Indian Reservation forms part of the northern boundary of the everglades. Is the Miccosukee River among the smaller almost inconsequential bodies of water comprising the everglades? Is Miccosukee River local or informal lingo used by the eyewitness? I don’t know that there is any inconsistency here if that is the case. Neither do I think the eyewitness is aiming for pinpoint geographic accuracy. As nothing else seems inconsistent, it doesn’t leave much else other than taking the testimony at face value—at least in an essay of this type—rather than outright dismissing it, unless further evidence to the contrary comes in, which is an invitation down the rabbit hole if there ever was one.

A tracking or radio collar is an indication of telemetry, which entails geospatial tracking of an animal. It is used to eliminate the human observer, which might influence an animal’s behavior in an unnatural way, and/or utilized when it is impractical, if not impossible, for an observer to follow an animal in its natural habitat, especially if the animal has a large home range or is associated with impenetrable terrain or migrates over vast distances. Data is the end goal and will almost certainly involve tracking the animal’s movements to determine its home range, associated habitat and accessible food resources, and within this, an inner core range where most time is spent.

Ground based radio telemetry locates an animal by signals from a transmitter within a radio collar or other device attached to the animal. It may involve a handheld receiver and antenna like those used by a wildlife biologist in the field when determining the location of a hibernating bear for example. More advanced telemetry is satellite based. Argos, a joint cooperative between the United States and France, utilizes polar satellites, one orbiting the northern atmosphere, the other orbiting the southern atmosphere. Signals are received from a transmitter and location is calculated by the Doppler effect and results are sent to a computer/computer operator. GPS satellite tracking, in contrast, sends signals from satellite to transmitter and location is calculated by triangulation of three or more orbiting satellites. Data is stored on the transmitter so it can be retrieved/retrievable by a wildlife biologist or someone in the field.

Technologies and capabilities are changing quickly in the telemetry field, and with the launch of so many privately owned corporate satellites an entire industry is growing around it. Telemetry studies have been conducted on all manner of species including birds, bears, elk, deer, moose, mountain lions, wolverines, bobcats, coyotes, dolphins, turtles, raccoons, etc.

A private corporation like Vectronic can provide a good overview of the most up-to-date GPS collar technologies and software involved. GPS collars capable of detaching remotely and collars with built-in cameras are now state of the art. The Vectronic website lists a more expansive list of animals that have been incorporated in telemetry studies using some variant of its GPS collars including lions, tigers, giant pandas, grizzlies, wild dogs, boar, bison, caribou, reindeer, leopard, wolf, etc.

Many telemetry studies of today also incorporate physiological collection of data, which can be correlated with GPS data and animal movements for an even more thorough understanding of animal behavior. Often, this entails an additional device implanted in the animal that can monitor functions such as heart rate, body temperature, blood pressure, activity levels, etc. Biotelemetry devices or biologgers are often capable of transmitting data like body temperature to a radio collar, which can be accessed when the collar is retrieved, as in a study done by Herberg, et al, (2018) where rumen implants were placed in moose.

Laske, et al, (2018), in contrast, collected heart rate data from implanted biologgers in black and brown bears by utilizing local, mobile telemetry stations, coordinating it with the larger GPS data in attempts to better understand when bears were exposed to stress in the environment. As Laske, et al, (2018) state, “Combining physiological data with concurrent GPS collar locations provided insights into the impacts of human and environmental stressors (hunting, predation by other bears, road crossings, drones), which would not have been apparent through spatial data analysis alone.” The biologgers that Laske implanted, which were adapted and modified from those used in humans, went through three iterations over the years, becoming smaller and more battery efficient and less susceptible to rejection, the last iteration only taking one stitch to close after implantation (Laske, et al, 2018). Laske, et al, (2018) envision the rapid technological advancement of biotelemetry devices, the increased memory of each device, and ever-increasing capabilities including “measurements of respiratory rates, thus enabling the potential for calculating of metabolic rates.” Although the Laske et al., (2018), study was restricted to brown and black bears, the authors state, “These biologgers are now being applied to other species, and the possibilities seem limitless as technologies continue to advance.”

Where does all this leave us? If this sighting is accurate and if this sighting is not a hoax, we almost must surmise that some branch of government and some agency therein operating in extreme secrecy possesses unparalleled bigfoot data degrees beyond that which is publicly available and published by current bigfoot researchers, with too much of the latter popular work, given to wild conjecture, unsubstantiated reasoning, or worse interlaced with the paranormal, but lacking any foundation in fieldwork, scholarly research, or data analysis. Such data obtained by an agency via telemetry could and may well include the aforementioned home range data, just how far—and how fast—a bigfoot travels, preferred habitats, food resources exploited in the home range, predatory data, aversion data (instances/methods to avoid humans), encroachment data into fringe human occupied zones, and potential interaction data (with members of its own species), all of which could be supplemented and more thoroughly understood by biotelemetry data and implants, perhaps modified from human implants as in the Laske study, or adapted as is for similar physiological data collection in the sasquatch, whether it be for heart rate monitoring, activity levels, blood pressure, and/or body temperature. Even some limited form of EEG (brain activity) monitoring may not be out of the question as Laske and his fellow researchers were also able to incorporate such data collection for hibernating bears. The limitless possibilities that Laske envisions for biotelemetry, especially as used in conjunction with satellite telemetry, would apply just as readily to the sasquatch as any other animal, if not more so given the amplified scientific consequences and the knowledge to be gained. With resources like Argos and/or GPS satellites and “off the books” financing that we must also envision as available to any such government agency, limitless possibilities become ever more the norm. Even a miniature camera embedded in or attached to a GPS collar is a possibility, like those shown on the Vectronic website.

All this goes without saying that if some team of government employees was logistically capable/logistically outfitted to attach a tracking collar to a bigfoot, then it would be equally capable of taking tissue, blood, hair samples, video/film, physical measurements, and anthropological observation/notes. With lab processing, the entire sasquatch genome could be sequenced, classified in relation to sapiens and neanderthalensis, for example, deviations mapped, archaic genes noted, the ancestral split calculated. It is not too far-fetched that with all this, perhaps supplemented with other observational data or a remote camera embedded in a collar, determinations could be made as to whether the sasquatch has speech capabilities and/or the capacity for protolanguage or gestural communication.

Although the above may be reasoning built upon suppositions that reach a logical endpoint, I have a strong visceral reaction against it. Beyond it being the stuff of rabbit holes—and near paranoia—it supposes the government has answers far in advance of science. There is something unredeemable about that to my mind. It suggests a colossal failure on the part of science and an irredeemable failure on its behalf in the art of inquiry and wonder. As tragically communal in thinking as the scientific community has been in all matters pertaining to the sasquatch, many bigfoot researchers, myself included, at least held out hope that the scientific community might yet vindicate itself at some point with a recalibration. When answers are now withheld from the scientific and public domains, where they rightly should be, it is far too late for any kind of recalibration, especially with what can only amount to a counterproductive intelligence at work to suppress discovery. Such discovery suppression would only serve to reinforce the stance that bigfoot is not a legitimate field of scientific study.

For any of this to hold water, it is not enough to examine eyewitness testimony or other pieces of evidence that may point to greater government involvement and potential suppression of the truth—there must be plausible explanations for it. Against my own better judgement perhaps, but indulging in this line of thinking nonetheless, circling back to the one piece of evidence of early government interest in the phenomenon, the 1975 Washington Environmental Atlas, may offer the best clue when placed in the historical context of the era, namely the Cold War. Again, the atlas relies to great extent on the data compiled by an outside researcher, John Green, so it seems a logical deduction that at this time the government was still in the early data gathering and supplemental data gathering stage, a stage where footprint evidence and the Patterson-Gimlin film were taken seriously, and the reality of the phenomenon was buttressed—perhaps—by physical evidence, a hair sample later denied by the FBI as being in its possession, though described in a very particular way as belonging to neither human nor known animal, which is oddly specific in the way it describes its lack of correlating traits and seems an indictment against it being a datapoint just plucked from thin air so to speak.

If the government had only limited sasquatch data but took seriously evidence of its existence—even if noncommittal—moving forward in covert study may have been the best option in the 1970s until it had a better understanding of the phenomenon. Unlike science, the intelligence apparatus may not have had the luxury of overlooking it given that the same phenomenon also reportedly existed in Soviet territory. Outside of North America, the best documented region for sasquatch sightings in Green’s Year of the Sasquatch (1970) is the Pamir Mountain range located in Tajikistan, part of the Soviet Union at the time, with at least three sightings, the region also the focus of an expedition led by the Russian hominologist Porshnev, the only geographic datapoint outside the American continent specifically singled out by the atlas. With the phenomenon occurring in each adversary’s territory, could it impact the Cold War in some way? While it might seem a leap, it could also prove irresponsible not to examine it from a national security standpoint. Even the slightest advantage might tilt the balance of power, especially since the use of animals for military purposes has a long history, with horses, camels, elephants, and pigeons utilized in the past to greater or lesser degree, dolphins and sea lions more modern embodiments (Gasperini, 2003), and dogs spanning ancient military use to modern warfare. The size, strength, fast agile movements, endurance, ability to see in the dark and cover a vast territory while leaving minimal trace that the atlas attributes to the sasquatch takes on new overtones in a military or espionage context.

Even if the sasquatch proved to have no utility in a direct operation of some kind, which seems the likely starting assumption by any U.S. intelligence agency, more intriguing—and potentially of greater value—would be if the sasquatch might confer some advantage in a secondary way, by gaining biological understanding of its night vision for example, whether it diverged in any fundamental way from other nocturnal animals, and whether some lesson here might lead to advancement in technology or operations. It’s akin to applying reverse engineering principles, where applicable, to a very unique biological entity, made so by its “distinctly humanlike form” to quote the atlas, in order to determine potential applicability to military or covert technology/operations. Could aspects of its strength be replicated and somehow applied to technology or tactics, even the biology of humans? Aspects of its speed? Endurance? Ability to canvas a large area? Presumed recovery abilities? Ability to move without leaving a trace? Ability to move without being seen? Ability to see and move in darkness? Ability to move in extreme terrain? If only one avenue of questioning yields insights that leads to applicability, it may be a potential intellectual gold mine from a bioengineering perspective. Studying any of these behaviors or biological processes remotely takes us back full circle into telemetry and biotelemetry studies, with the incorporation of tools like satellites and radio collars, only with the aims being specifically military or espionage in application.

While Cold War concerns may be a logical starting point when considering reasons for government classification from a historical perspective, whether military or espionage concerns would still hold true today would rely on the discovery process and the advancements therein, which could be substantial if telemetry has been incorporated. Whatever the goals, any study of the sasquatch would be a scientific program first and foremost involving personnel from the biological sciences. The greater the disruption the sasquatch has upon the current scientific paradigm, the greater the likelihood of continued secrecy. In such a scenario, a rapid evolution from the more laissez-faire attitude of the atlas to “lock down” or high classification mode would be expected, made more so from the unwitting public interest the atlas provoked. The answers as to why this would be the case can best be inferred from the domains of science the sasquatch would impact and the degree to which it would disrupt them, dependent, of course, on precise taxonomic classification of the sasquatch. If the sasquatch is determined to be a great ape as proposed by other bigfoot researchers, a descendent of Giganto or some other yet unknown Asian ape species, which convergently developed bipedalism, while important, it is much less so in comparison to shared hominin ancestry with humans, should the latter be determined—and potential classification within the Homo genus. The latter discovery not only upends the entrenched anthropological paradigm of Homo sapiens being the sole extant hominin species, demanding a scientific reset—a trial in and of itself because it is so philosophically entrenched—but also comes with an entire cohort of moral, legal, societal, national, political, economic, environmental, and religious consequences. In addition to the obvious impact upon anthropology and subdisciplines like paleoanthropology, biological anthropology, and linguistic anthropology, ramifications are likely in many, if not all, of the following fields:

- Primatology

- Zoology

- Wildlife biology

- Ecology

- Evolutionary biology/evolution

- Genetics

- Conservation biology

- Biological engineering

- Neuroscience

- Cognitive science

- Psychology

- Anatomy/Physiology

- Biolinguistics/linguistics

- Biomechanics

- Biomedical research

- Cognitive biology

- Developmental biology

- Pathology

- Biotechnology

- Sociobiology

If a numeric scale from 1-10 was used to assign a classification level to the sasquatch if it derived from the Homo genus, for genomic knowledge/mapping alone, and the resultant potential of biological engineering as just one example, I would assign the species a classification level of 10. In many ways, although it sounds like the stuff of science fiction, the species would be an extant genetic hominin reservoir, critical in both understanding and preserving, while also not letting such genomic knowledge into the hands of adversarial governments. If interspecies communication is possible, whether through a protolanguage or proto-gestures, or an even more complex sign language, then classification at the highest level is justified even more.

Although this is all admittedly hypothetical, I see a significant drop-off in classification level for the sasquatch if determined to be another great ape, albeit a highly unusual one with bipedal adaptations. The main interests in such a case would be biomechanical and bipedal locomotion, with genomic interest primarily centered upon this aspect. As for the remainder of the genome, it would represent an ancient divergence like that of the orangutan, older than both the chimpanzee and gorilla, with interest and importance being on a similar level to the orangutan. Like the orangutan and the other great apes, speech capabilities would be lacking owing to a more primitive vocal tract and lack of basicranium arching (roof of mouth), unless it has undergone convergent evolutionary changes in anatomy here as well, an extreme unlikelihood. In terms of what it means to be human, it is significantly devalued. It is less anthropological discovery and more anthropoidal discovery. In fact, many reasons for government classification fall away, though there could still be more limited military/espionage implications. While I don’t see the Giganto hypothesis as plausible (see Bigfoot in Evolutionary Perspective, Chapter 6, this site), since it is the prevailing thesis of most bigfoot researchers it needs to be addressed. I’d assign the species a classification level of 4 to 5 in the great ape scenario, the argument for the government to maintain classification more difficult, perhaps the result of little more than longstanding agency tradition, the bigfoot phenomenon not entirely without implications, but, all in all, more mild in societal, scientific, and national security terms. If there is any conspiracy in such a scenario, it suggests an economic-environmental one.

In the final analysis, this is a highly speculative essay. In order to establish continued—and far reaching—government interest in the bigfoot phenomena, it is almost entirely dependent on either the Battle Mountain incident as described by Powell (2003) or the “Everglades incident” as detailed in Isdahl (2020) containing accurate eyewitness testimony. There may be other incidents that also suggest government involvement, though none as compelling as either of these—at least that I am aware. Others, like Fred Bradshaw’s Mt. Saint Helen’s secondhand account are riddled with so many fallacies that they establish themselves as hoaxes almost by default. That reduces this essay to an exceedingly small dataset and a whole lot of “ifs”—certainly too many “ifs” for my liking and not nearly enough eyewitness data, and I’m sure many readers will feel the same way, though I do feel the reasoning is sound along the way, enough that I can say if the government has been involved in covert sasquatch research over the course of the last fifty years—certainly an extensive timeframe upon which to build—telemetry studies are the logical endpoint for any agency with comparatively unlimited resources at its disposal. Maybe further proof or refutation will come to light in the future about either of these other two eyewitness incidents, and just as likely there will be nothing more. Such is the nature of the bigfoot phenomenon.

My instinctive reaction is to dismiss the whole government conspiracy thing. While it is as an overarching explanation that resolves the continued elusiveness of the hominin by suppression of the truth, it is an also an unsatisfactory one from a scientific standpoint and, admittedly, this is where my bias lies. Bigfoot speed, camouflage, active evasiveness when in proximity to humans, other biological, as well as ecological principles just as readily explain the species continued elusiveness, not to mention a certain egotism on behalf of scientists. In Bigfoot in Evolutionary Perspective, I pointed out that when science abdicates its duties, paranormal explanations start to creep in, proposed by those less versed in the sciences. So too, when science abdicates its duties, government conspiracies can also creep in. There is a difference here though. Government agencies are tangible, and as for the bigfoot phenomenon itself, they do exist as a fringe element as demonstrated by the atlas and the FBI’s response to Byrne, and outside of that, if only in hearsay and a few cases of eyewitness testimony for the most part. Ultimately, I can’t dismiss the possibility that the government is involved in the bigfoot phenomenon. Acknowledging that doesn’t make one a conspiracy theorist. Neither can I outright dismiss two of the most intriguing eyewitness incidents as presented—the Battle Mountain incident and the “Everglades incident”—at least not without further information to analyze. In the end, the reader will have to weigh this analysis—limited as it is—for him/herself, draw his/her own conclusions, if any, and supplement this analysis with outside data or perhaps even personal life experiences.

[1] There seems to be a bit of a discrepancy as to the elder Bradshaw’s job title. Coil Suchy (2009) states he is a supervisor, while Short (2012) quotes Fred Bradshaw saying his father worked security. Perhaps the elder Bradshaw worked in a supervisory security position, in which case there is no discrepancy. I mention this because the narrative takes on different overtones depending on what Bradshaw’s precise job title is.

[2] This encounter included a weight estimated for the bigfoot Bradshaw encountered, and I used it in Bigfoot in Evolutionary Perspective , along with other weight estimates reported by other eyewitnesses to demonstrate the variation in weights eyewitnesses report and how difficult it is for eyewitnesses to give accurate weight estimates for a bigfoot. Since John Green only reported two bigfoot encounters for Fred Bradshaw in his database, I was not alerted to the many other incidents as reported in Short, as well as the incident Moriarity reported. I will remove the reference in any future editions, since Bradshaw in unreliable.

References

Aho, B./U.S. Navy. (2003, September). [Photograph]. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/uncle-sams-dolphins-89811585/

Bagley, M. (2018, October 16). Mount St. Helens eruption: Facts & information. In Live Science. Retrieved from https://www.livescience.com/27553-mount-st-helens-eruption.html

Bigfoot part 01 of 01 (n.d.). In FBI Records: The Vault. Retrieved from https://vault.fbi.gov/bigfoot/bigfoot-part-01-of-01/view

Coil Suchy, L. (2009). Who’s Watching You: An exploration of the Bigfoot phenomenon in the Pacific Northwest. Blaine, WA: Hancock House Publishers LTD.

Engineers Corps book recognizes ‘Big Foot’. (1975, July). Washington Star-News.

Fountain, P. (2021, February 11). They’re Arctic survivors. How will they adapt to climate change? New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/02/11/climate/wolverines-climate-change.html

Gasperini, W. (2003, September). Uncle Sam’s Dolphins. Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/uncle-sams-dolphins-89811585/

Green, J. (1970). Year of the Sasquatch. Agassiz, Canada: Cheam Publishing Ltd.

Herberg, A. M., St, louis, V., Carstensen, M., Fieberg, J., Thompson, D. P., Crouse, J. A., & Forester, J. D. (2018). Calibration of a rumen bolus to measure continuous internal body temperature in moose. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 42(2), 328–337. DOI: 10.1002/wsb.894

Isdahl, S. (2020). The day Sasquatch became real for me.

Kenck-Crispin, D. (2016, October 21). The government is hiding dead Bigfoot bodies!! In Orhistory.com. Retrieved January 6, 2021, from https://orhistory.com/archives/5658

Krantz, G. (1999). Bigfoot Sasquatch evidence: The anthropologist speaks out (2nd ed.). Surrey, Canada: Hancock House Publishers.

Laske, T. G., Evans, A. L., Arnemo, J. M., Iles, T. L., Ditmer, M. A., Fröbert, O., Garshelis, D. L., & Iaizzo, P. A. (2018). Development and utilization of implantable cardiac monitors in free-ranging American black and Eurasian brown bears: system evolution and lessons learned. Animal Biotelemetry, 6(1), N.PAG. DOI: 10.1186/s40317-018-0157-z

Lyman, R. L. Taphonomy of cervids killed by the May 18, 1980 volcanic eruption Mt. St. Helens, Washington, U.S.A. Bone Modification, 149-167. Retrieved from https://faculty.missouri.edu/~lymanr/pdfs/1989MtStHelenstaphonomy.pdf

Mather, P. (2021, February 11). [Photograph]. New York Times, New York. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/02/11/climate/wolverines-climate-change.html

Moriarity, L. (2000, September 27). Bigfoot’s fans keep close tabs on his annual Northwest tour. The Daily Herald. Retrieved from https://www.heraldnet.com/news/bigfoots-fans-keep-close-tabs-on-his-annual-northwest-tour/

Napier, J. (1973). Bigfoot: The Yeti and Sasquatch in myth and reality. New York, NY: E.P. Dutton & Co,, Inc.

Paulides, D. (2008, December 8). The Bigfoot interview. In North America Bigfoot Search. Retrieved January 24, 2021, from https://www.nabigfootsearch.com/Bigfootdisclosureproject.html

Paulides, D. (2008). California Department of Fish & Game/ The Bigfoot file contents. In North America Bigfoot Search. Retrieved January 24, 2021, from https://www.nabigfootsearch.com/Bigfootdisclosureproject.html

Powell, T. (2003). The Locals: A contemporary investigation of the Bigfoot/Sasquatch phenomenon. Surrey, Canada: Hancock House Publishers LTD.

Short, B. (2012). The de facto Sasquatch. Retrieved from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/596c0bae4c0dbfa1d26e86be/t/5b9bff06562fa7cfcdf1bfc8/1536950038606/The+de+facto+Sasquatch+premier+installment.pdf?fbclid=IwAR3763B1leKUEQofPRbPvzAItNH5K-RUVoKU-vO

United States Army Corp of Engineers. (1975). Washington Environmental Atlas (2nd ed.). Washington D.C.: Author. Retrieved from https://documents2.theblackvault.com/documents/usace/Washington1975Atlas-Sasquatch.pdf

USGS/Cascades Volcano Observatory. Spirit Lake [Photograph]. Mt. St. Helens Science and Learning Center. http://www.mshslc.org/gallery/lakes/

Wilson, T. A. (2015). Bigfoot in evolutionary perspective: The hidden life of a North American hominin. North Charleston, SC: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Copyright 2021, T.A. Wilson, all rights reserved.